The recently completed bark house and Native American encampment in Ward-Meade Park were formally dedicated in a recognition ceremony on Friday, October 14, 2022. The bark house and encampment are the newest additions to Old Prairie Town, located at the Ward-Meade Historical Site in Topeka, Kan., which hosts recreations and replicas of several other 1800s-style structures.

10.14.22 — PBPN Tribal Council Member Tony Wahweotten views the Native American encampment site before the recognition ceremony, with the bark house in the background.

The bark house was built in the traditional style of a Potawatomi wigwam, and its construction was led by Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation tribal member Mi-Kes Potts. Citizen Potawatomi Nation Legislator Jon Boursaw also had a lead role in developing the encampment project and provided expertise to guide historical accuracy and respectful representation of tribal cultures in Kansas.

Along with the bark house, the encampment includes a campfire area, a Medicine Wheel, and a garden. The recognition ceremony consisted of remarks from those involved with the development of the encampment project and public officials, a blessing of the encampment in the form of smudging by Boursaw, and performances by the Royal Valley Native American Singers and Dancers.

10.14.22 — Members of the Royal Valley Native American Singers and Dancers stand to watch the first part of the recognition ceremony.

The Ward-Meade Historical Site, which also features the Ward-Meade Mansion and Ward-Meade Botanical Garden, is managed and maintained by the Shawnee County Parks and Recreation Department. The grounds have been developed to preserve and teach the story of pioneer and wheelwright Anthony Ward and related early Kansas history.

Ray Schroeder, a long-time Shawnee County Parks and Recreation employee who had a lead role in developing the encampment project, highlighted the importance of the addition at the recognition ceremony, saying, “We at Prairie Town tell a story, and for the most part, I think we’re pretty good at it. But that story has obviously been incomplete.”

During the welcoming remarks, John Bell, Recreation Program Supervisor for Old Prairie Town, also described Native American representation as “the missing link” at the park.

“For the past 46 years, most of the history told at this site only focused on the Ward-Meade family, specifically life after 1854 when Anthony [Ward] purchased 240 acres of land from Kaw tribesman Joseph Jim for 140 dollars,” Bell said. “The history of the site, of course, predates that by many transactions. Today, we’re putting one of the missing puzzle pieces in place, so we are able to tell the rich history of this land that we stand on today.”

Shawnee County Commissioner Bill Riphahn echoed this sentiment, saying, “It’s impossible to tell the history of an early Kansas town without telling the story of Native Americans.”

Although the land on which Topeka was built has been home to several tribes, including the Potawatomi, Kaw, Shawnee, and Osage, Native Americans’ stories had previously been unrepresented at Ward-Meade Park. Native Americans have often had to fight for representation on two fronts: first, to have their histories told without distortion, and second, to be recognized as present-day peoples who continue to keep their cultures and traditions alive today.

10.14.22 — PBPN Chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick speaks about Potawatomi history during the recognition ceremony.

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick illustrated Native Americans’ struggle with examples from Potawatomi history during his speech in the recognition ceremony.

“One of the things that a lot of folks don’t realize is that where we come from and how we got here is through a series of treaties,” Chairman Rupnick said. “The Potawatomi people have the most treaties ever signed with the United States government. We have over 40 treaties that were signed. Every one of them had been broken in one form or fashion or another.”

He went on to describe the series of treaties that led to the Potawatomi people being removed from their ancestral land and forcibly relocated, with the Prairie Band eventually arriving at their current lands north of Topeka on what had originally been Osage land.

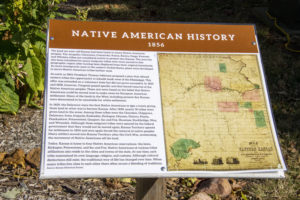

10.14.22 — One of the signs at the encampment describes the history of the various tribes in Kansas, including information on forced removal and broken treaties.

He pointed out that the new bark house was very similar to the first semi-permanent structures that the Prairie Band Potawatomi built before constructing more permanent dwellings.

“I know that—talking with some of the Elders that we had—they were a little apprehensive about being able to build one of these and share it and share our history, just because, anymore, we mostly use these for some of our religious and ceremonial services,” Chairman Rupnick explained. “So it was good that we progressed beyond that to allow us to share our story.”

“This is an art that has really kind of been forgotten,” Chairman Rupnick said. “We’re starting to bring that back and utilize it again.”

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Legislator Jon Boursaw discussed the development of the encampment project. He said that, when he was first consulted for the project, the initial request was for a teepee, but that the Potawatomi “were not teepee people.”

After adjusting plans accordingly, he brought Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation tribal members Mary LeClere and Lavera “Babe” Bell into the project, who in turn reached out to Mi-Kes Potts because of his knowledge of traditions and construction experience.

10.14.22 — Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Elders Lavera “Babe” Bell (left) and Mary LeClere (right) pose for a picture in front of the bark house. They were recognized during the dedication ceremony for their contributions to the encampment project.

Potts said that the request to build the traditional structure struck a chord with him. “Our people need this. The people need this. We need to show the world who we are.”

“Our people were known to adapt. We adapted a little too much, lost our old ways,” he went on to say. “You get the opportunity to do something like this—do it! Help people with the knowledge.”

10.14.22 — Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation tribal member Mi-Kes Potts speaks about his experience building the bark house.

While the construction of the bark house will help preserve traditional knowledge for the Potawatomi people, the encampment will also educate non-Natives on Native American culture and history. There are three signs with information about the Medicine Wheel and Native American history at the encampment site.

Boursaw spoke to the importance of consulting tribal members in the development of the encampment project and foregrounding the true histories of tribes in Kansas by relating the story of a Kansas Historical Society event he attended, during which a speaker referred to “wild Indians” living in the Topeka area when Cyrus Holiday helped found the town.

“Did you know that during that period of time, we had two schools?” Boursaw asked. “We had the school at the Baptist Mission, which is basically now the Kansas Historical Society. And the Catholics had a school at St. Mary’s, and the town followed after the school was established. We weren’t running wild through what is now West Topeka. We lived here. This was our land. And I’m proud to bring back part of our land.”

Following the remarks from the speakers, Boursaw blessed the encampment by smudging. Afterwards, the Royal Valley Native American Singers and Dancers closed out the recognition ceremony with a performance of several songs and various dance styles, ending with an intertribal dance that friends and family were invited to join.

10.14.22 — The Medicine Wheel at the Native American encampment at Ward-Meade Park. Citizen Potawatomi Nation Legislator Jon Boursaw explained that the Medicine Wheel “contains the gifts given by the Creator to mankind.” The plants growing within the Medicine Wheel are sweet grass, tobacco, cedar, and sage.

10.14.22 — Citizen Potawatomi Nation Legislator Jon Boursaw fans the smoke with eagle feathers while smudging. The herbs burned in the shell are the same found in the Medicine Wheel: sweet grass, tobacco, cedar, and sage.

10.14.22 — The Royal Valley Native American Singers and Dancers perform at the closing of the recognition ceremony.

10.14.22 — The Royal Valley Native American Singers and Dancers perform at the closing of the recognition ceremony.